VI. Jazz

77

Megan Lavengood

Key Takeaways

This chapter presents two ways of adding new harmonies to an existing chord progression.

- An applied ii chord, as in the ii–V–I schema, can be used to embellish a dominant-quality chord. In other words, preceding a dominant-quality chord with the mi7 or ∅7 chord a fifth above it creates the effect of a ii–V.

- Common-tone diminished seventh chords (CTo7) create neighboring motion in all voices that embellish a chord. The root of the chord of resolution is always shared as a member of the CTo7—hence the term “common tone.” (Note: See this chapter for more information on CTo7 chords in Western classical music.)

Jazz performers often aim to add their own twist to existing jazz standards. One way of doing this is to add new chords that embellish existing chords in the progression. This chapter explores two ways that performers improvise by embellishing harmonies in jazz.

This chapter will use the opening few bars of “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington (1930) as a backdrop and add embellishing chords to it. If you take a moment to familiarize yourself with the tune, the following discussions will make more sense. Listen to Louis Armstrong’s interpretation of this song, embedded below, while following the chords of the first few bars, given here.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/10006141/embed

Example 1. Chords for the first four measures of “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington.

Embellishing Applied Chords

Applied V7

Any chord in a progression can be embellished by preceding it with an applied dominant chord. Example 2 takes the surprising G♭ chord of measure 7, divides it in half, and replaces the first half note of the chord with its applied V7 chord. In principle, this can be done with any chord in the progression.[1]

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/5719733/embed

Example 2. Inserting a D♭7 chord before the G♭7 chord creates an applied V of G♭, which is not present in the original chord progression of “Mood Indigo.”

Applied ii

The chapter on ii–V–I discusses the use of applied ii–V–Is, i.e., ii–V–I progressions that occur in keys other than the tonic key. Many jazz tunes have these applied ii–Vs built in, but a performer could add their own as well. A dominant chord can often be embellished by adding its ii chord before it, transforming it into a ii–V schema.

“Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington begins with the progression B♭–C7–Cmi7–F7–B♭. That first C7 could be embellished by adding a Gmi7 before it, creating a temporary ii–V that then proceeds to another ii–V. Rhythmically, this means cutting the duration of the C7 into two halves and replacing the first half with the applied ii chord. The result is the progression in Example 3 below.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/5719690/embed

Example 3. Inserting a Gm7 chord before the C7 chord creates a ii–V in F, which is not present in the original chord progression of “Mood Indigo.”

Common-Tone Diminished Seventh Chords (CTo7)

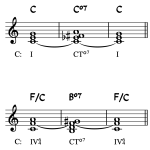

The common-tone diminished seventh chord (hereafter CTo7) is a voice-leading chord, which means that the chord is not based on a particular scale degree like most other harmonies, but rather the result of more basic embellishing patterns. In this case, the embellishing motion is the neighbor motion. To create a CTo7, the root of the chord being embellished is kept as a common tone (hence the name), and all other voices move by step to the notes of the diminished seventh chord that includes that common tone. This is best explained in notation, as in Example 4.

The CTo7 can be used to prolong any chord. Rhythmically, the chord would be inserted somewhere in the middle of the total duration of the harmony, leaving the prolonged harmony on either side of it (as in Example 4). Another option is to skip the initial statement of the prolonged harmony and instead jump straight into the CTo7. Example 5 adds both types of CTo7 to “Mood Indigo,” the melody of which is particularly suggestive of CTo7 embellishments. In this example, the CTo7 chords are not given their own Roman numerals, to show that they do not significantly affect the harmonic progression of the phrase—instead, they embellish the chords around them with chromatic neighbor tones. Similarly, the CTo7 chords are not shown with chord symbols, because these chords are often not written into lead sheets but improvised by the performers.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/10006099/s/O6ycuv/embed

Example 5. A CTo7 embellishes the opening B♭ chord, inserted on beat 3 of the whole-note harmony. A CTo7 also embellishes the C7 chord, displacing the C7 by a half note.

Embellishing Chords in a Lead Sheet

As with substitutions, embellishments are not always represented the same way in a lead sheet.

- There may not be any embellishing chord notated, and instead, the performers are improvising this addition as they play.

- The embellishing chord may be built into the chord progression and thus be notated in the chord symbols.

- The embellishing chord may be indicated as an alternate harmonization and shown in the chord symbols with parentheses around the embellishing chords.

This is illustrated in Example 6 with different ways of showing a CTo7 in “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6656170/embed

Example 6. Embellishing chords can be (a) unwritten and improvised by performers, (b) written into the chord symbols, or (c) indicated as an alternative harmonization with parentheses.

- Levine, Mark. 1995. The Jazz Theory Book. Petaluma, CA: Sher Music.

- Bebop composition. Asks students to build on knowledge of swing rhythms, ii–V–I, embellishing chords, and substitutions to create a composition in a bebop style.

- PDF: Complete instructions + template

- MSCZ: Template for lead sheet, template for voicings

- DOCX: instructions only

- The G♭ chord is itself a tritone substitution for C7, which would be the applied V7 of F7. Tritone substitutions are discussed in another chapter. ↵

ii⁷–V⁷–Imaj⁷ in major, or iiø⁷–V⁷–i⁷ in minor. A fundamentally important progression in traditional jazz.

The button below is a link to download all worksheets from the textbook as a single PDF.

This file may be useful if, for example, you do not have reliable internet, or you are simply browsing the whole workbook at once. But in general, we recommend using the links at the end of each chapter instead of downloading this file. This is because:

- The PDF may not have the most up-to-date assignments. This is a static file, meaning that has to be manually re-uploaded to make changes—it is not automatically generated.

- The PDF has been compressed to reduce the file size. Some images or text may be compromised from this process.

Last updated: June 30, 2021

This section introduces students to the basics of music notation, including rhythm, pitch, and expressive markings. Students also learn to construct and identify rudimentary harmonies, including intervals (two-note chords), triads (three-note chords), and seventh chords (four-note chords).

Prerequisites

The Fundamentals section assumes no previous familiarity with Western musical notation. However, each chapter in this section assumes familiarity with all preceding chapters; for that reason, it is recommended that chapters are studied in order.

Organization

In the section's first chapter, Introduction to Western Musical Notation, students are encouraged to think about the ways in which they might write down (or notate) their favorite song or composition. The next six chapters (Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines through Other Aspects of Notation) focus upon the notation of pitch and the expressive and stylistic conventions of Western musical notation.

Next, students are introduced to the conventions of Western rhythmic notation in the subsequent four chapters (Rhythmic and Rest Values through Other Rhythmic Essentials). Pitch is then revisited, beginning with the spelling and identification of scales, key signatures, the diatonic modes, and the chromatic collection (in Major Scales, Scale Degrees, and Key Signatures through Introduction to Diatonic Modes and the Chromatic "Scale").

The following chapter, The Basics of Sight-singing and Dictation, presumes knowledge of the concepts in all previous chapters. It can be used as a stand-alone chapter in an aural skills class or within the context of a music theory or fundamentals course. Finally, the construction of harmonies is explored, from two-note Intervals through four-note Seventh Chords.

The Triads and Seventh Chords chapters deliberately do not include inversion or figured bass, as this is covered as a separate topic (Inversion and Figured Bass). This chapter, along with Roman Numerals and SATB Chord Construction and Texture, can be used as introductions to part-writing, counterpoint, music appreciation, or music history courses.

Audience

The Fundamentals section is designed for a wide audience, including high school students (and those taking AP Music Theory), collegiate non-music majors (and musical theater majors), and collegiate music majors.

A type of motion where a chord tone moves by step to another tone, then moves back to the original chord tone. For example, C–D–C above a C major chord would be an example of neighboring motion, in which D can be described as a neighbor tone. Entire harmonies may be said to be neighboring when embellishing another harmony, when the voice-leading between the two chords involves only neighboring and common-tone motion (as in the common-tone diminished seventh chord).